At PaperKite we’ve seen organisations struggle over and over again with problems that have their roots in an ineffective, incomplete, or non-existent product strategy. Do any of these problems sound familiar to you?

While putting effort into improving (or developing) your product strategy isn’t a guaranteed panacea for all these problems, it will go a long way to reducing them.

Before we dive into some product strategy problems and solutions I think it’s important to be really clear about what strategy is, because the term strategy is often misused and misunderstood.

There are plenty of different definitions out there. I like this one from straight-talking strategy consultant Richard Rumelt’s insightful and readable book, Good Strategy/Bad Strategy, because it captures the purpose and substance of strategy:

a coherent set of analyses, concepts, policies, arguments, and actions that respond to a high-stakes challenge.

There’s a lot in that short definition, so let’s pull it apart a bit.

Strategy is about working out how to respond to a high-stakes challenge. A high-stakes challenge will almost inevitably be complex, meaning that there will be many parts to it and those parts will be interrelated.

The complexity of the challenge means that there’s no self-evident response. Therefore strategy has to be multifaceted (analyses, concepts, policies and arguments) in order to work out what an effective response might be.

Finally, the actions are a crucial – and often neglected – part of strategic thinking. Without a plan with feasible actions, you don’t have a strategy. At best, you’ll have an idea of where you want to go, but no idea of how you’ll get there.

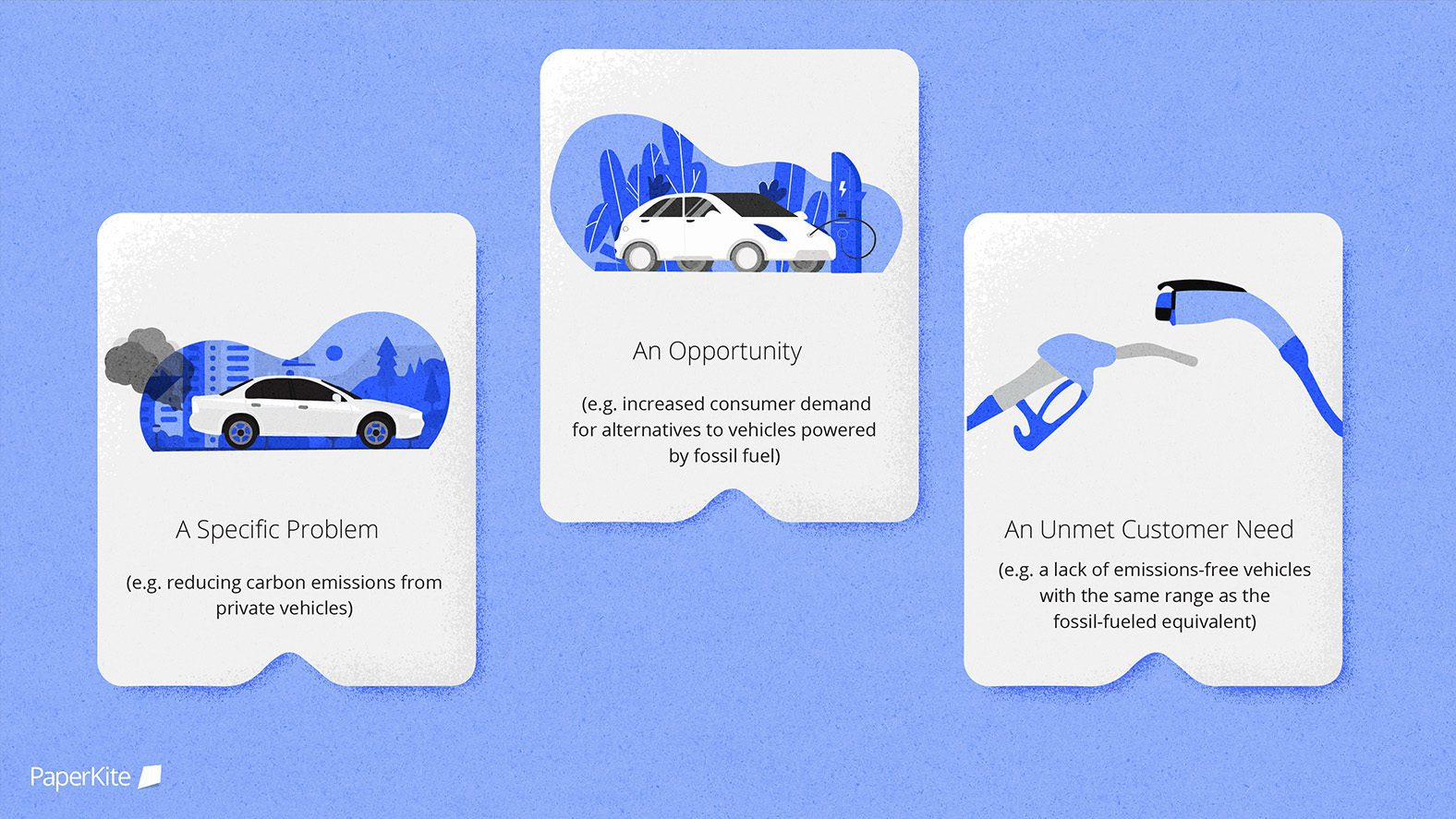

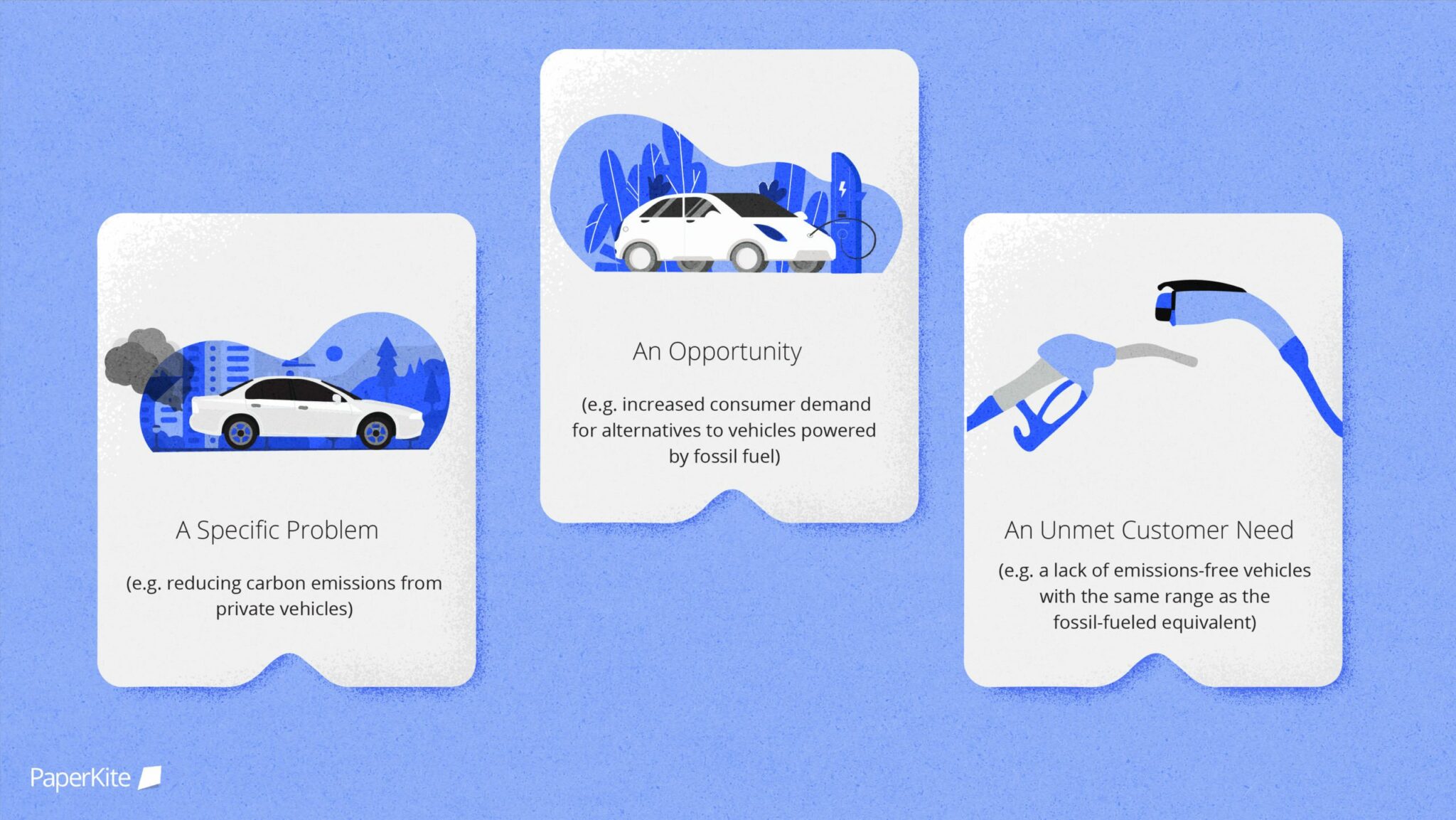

There are as many different fields of strategy as there are human endeavours. What they all have in common is the overall purpose: the need to respond to a challenge. A challenge can be framed as:

Further on in Good Strategy/Bad Strategy, Richard Rumelt summarises his view on what lies at the heart of good strategy, framing the challenge as a problem:

The kernel of good strategy is a diagnosis (of a problem), a guiding policy (your general approach to addressing the problem) and coherent action.

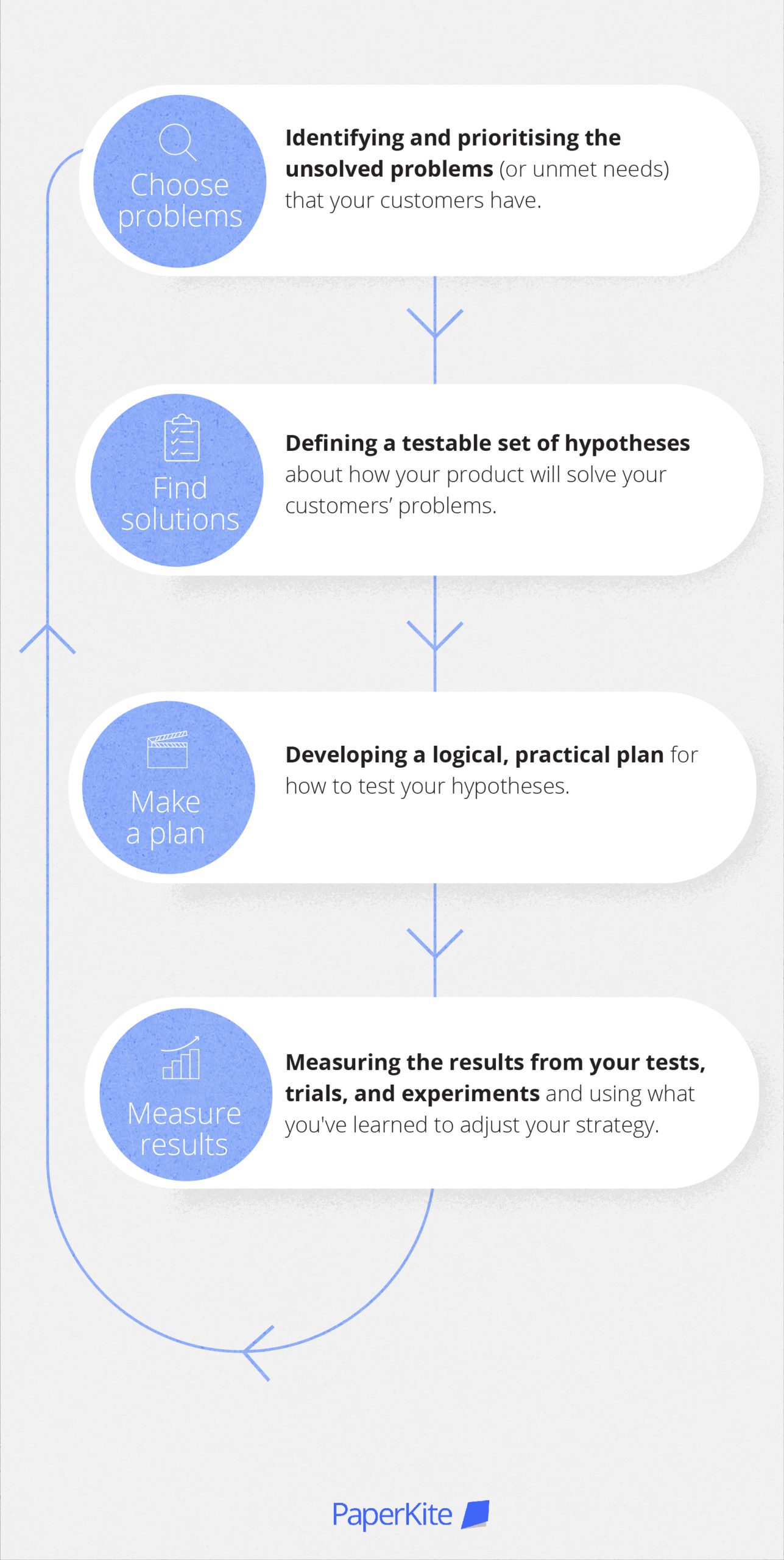

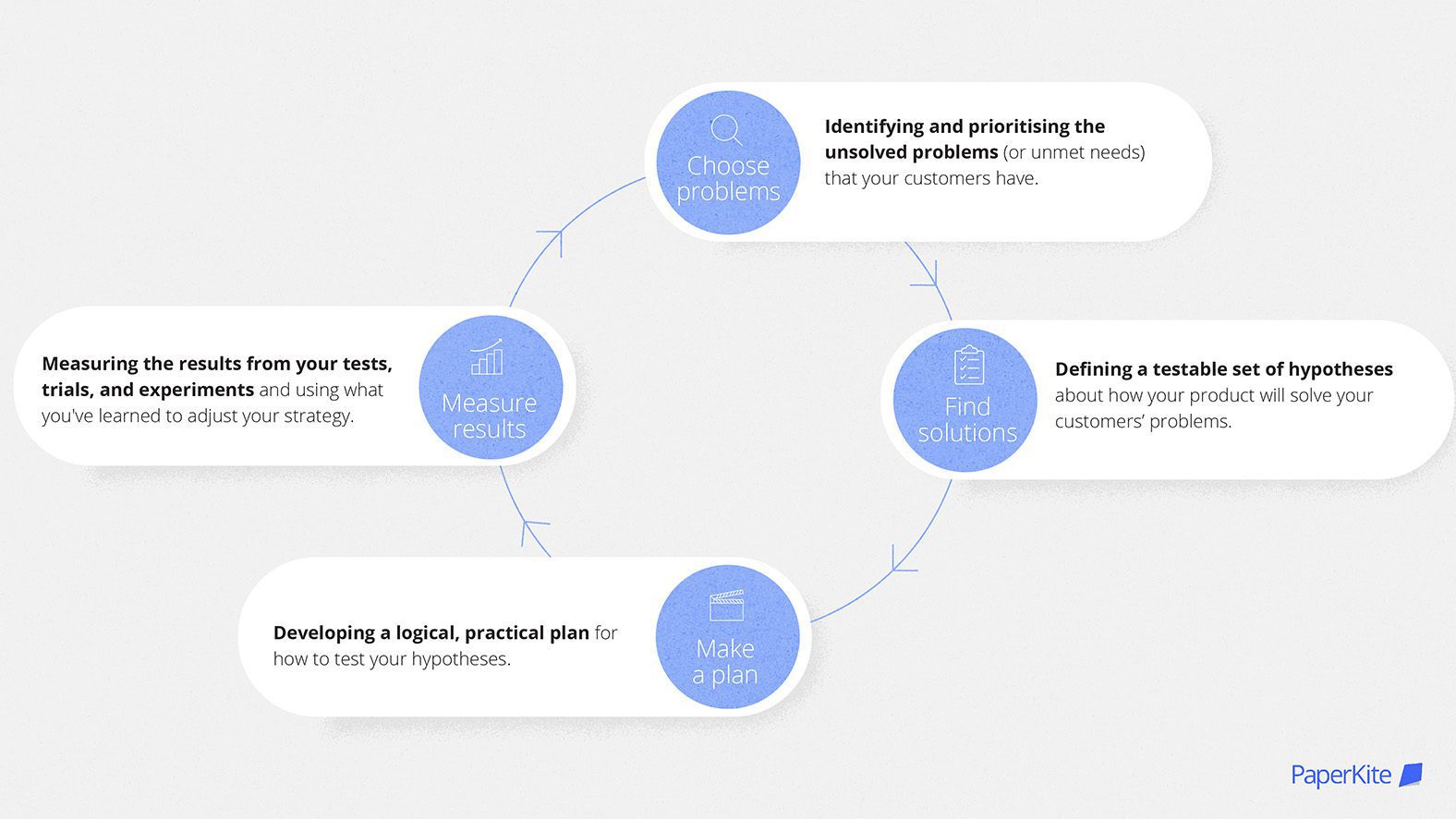

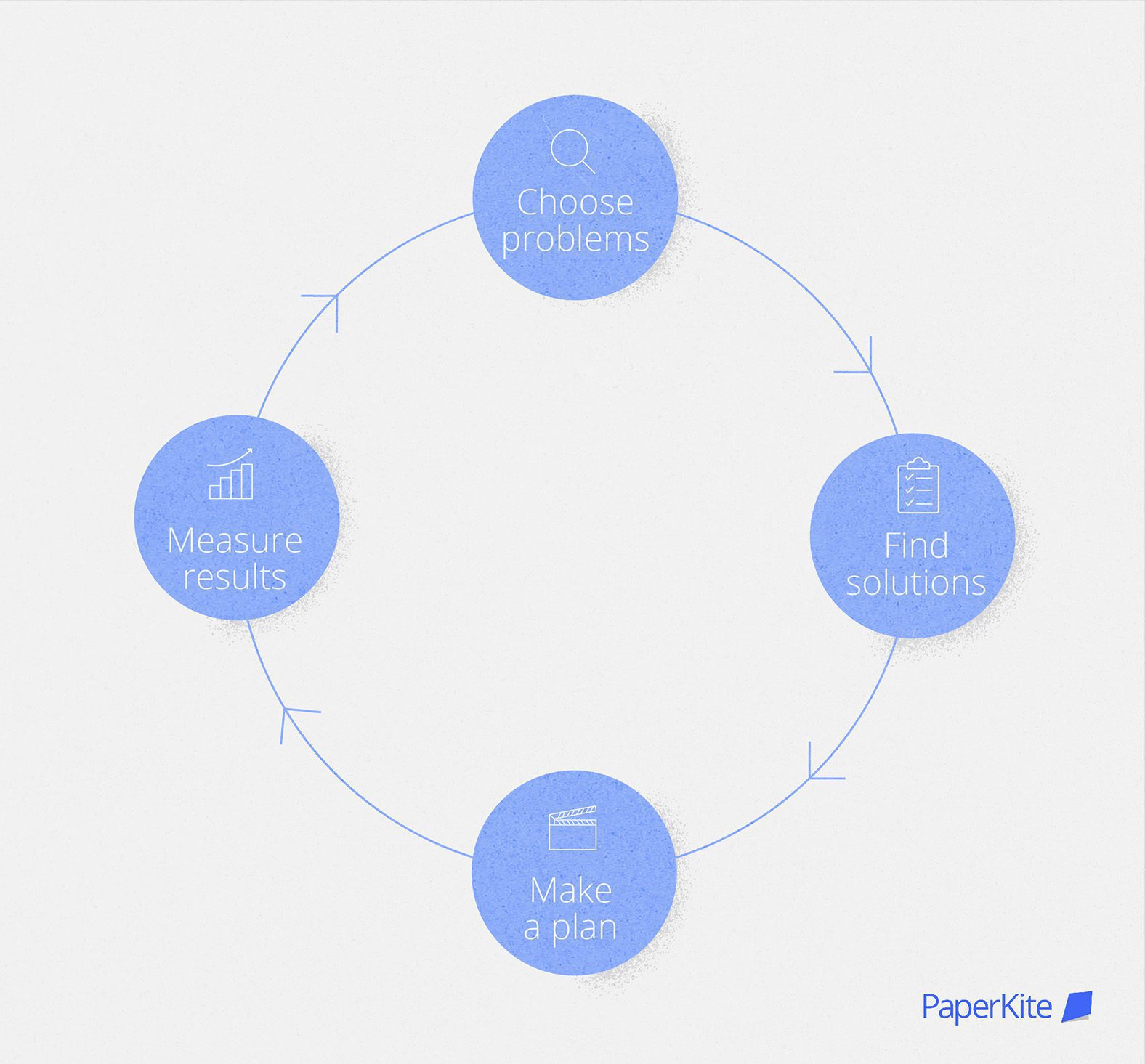

A hallmark of product strategy is its focus on the people who will be using (and usually paying for) your product. Taking Rumelt’s overall framing of good strategy and building on it, in my experience good product strategy is about:

Put another way, the basis of good product strategy is: identifying a worthwhile customer challenge, devising a series of informed hunches about how you can respond to the challenge, coming up with a plan to validate or disprove your hunches, and defining how you’ll measure if your hunches were right or not.

The need to come up with hypotheses (or hunches) is a crucial part of product strategy.

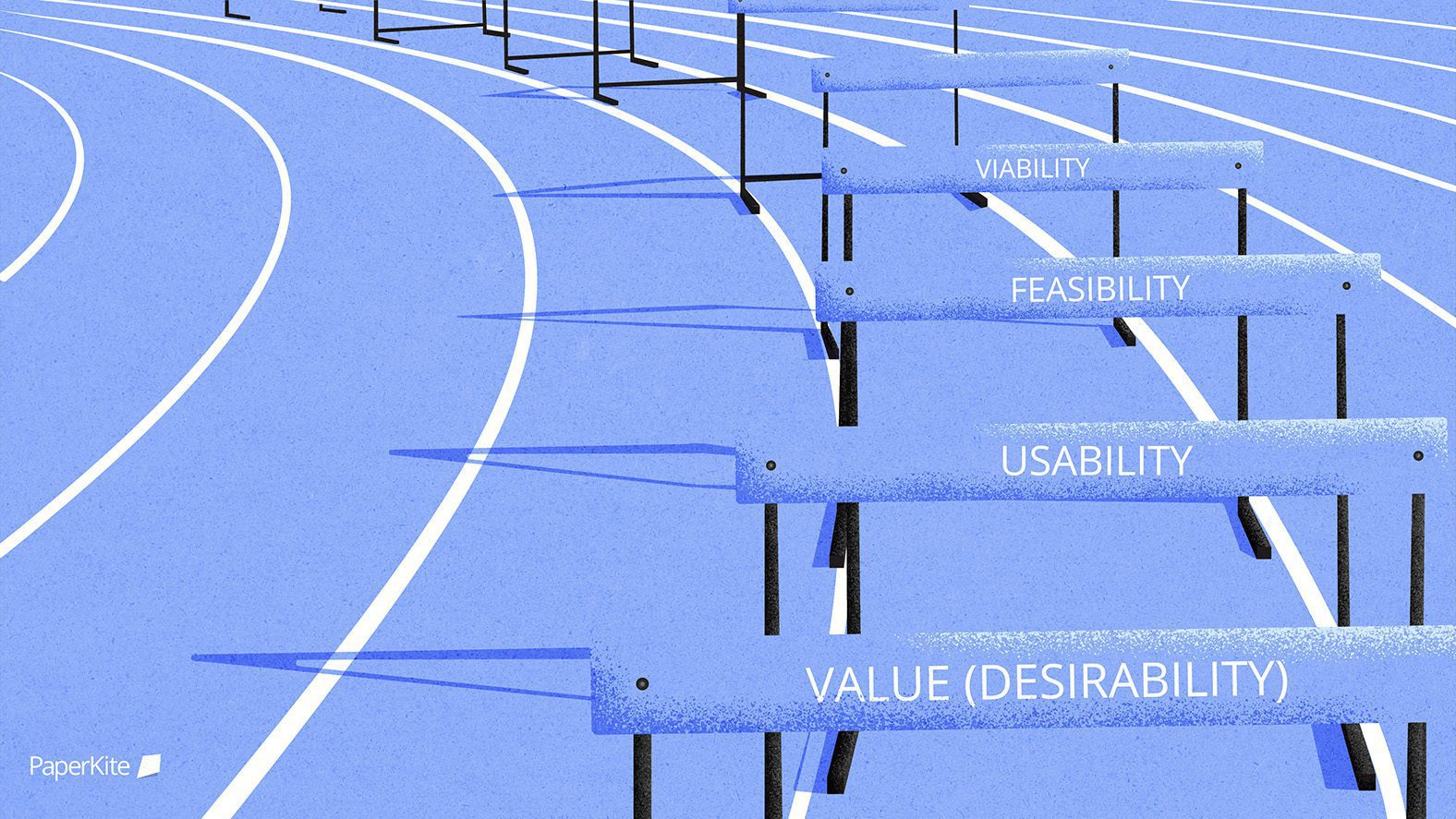

Sometimes the problems that we’re trying to solve with product strategy may appear simple, for example: “how can our product help our customers do X?” But a successful product solution to that problem must address the four big product risks that Marty Cagan outlined in his second edition of Inspired: How to Create Tech Products Customers Love:

While you might identify a solution that solves a user problem and that people will pay for (desirability), you would still have another three significant hurdles to get over in order to come up with a product solution that will work in the real world. That is a high bar to get over.

It’s not surprising then that, as Marty Cagan has also pointed out, at least half of our hunches about digital product solutions won’t work out. If that’s not sounding bad enough, Cagan also tells us that even if a product hunch turns out to be valuable, usable, and feasible it can take multiple iterations to get it to the point where it delivers value to the business. And all these iterations will cost more money and time, increasing the investment required to get to viability.

So, a lot needs to go into the mix when trying to develop an effective product strategy. You first need to identify and define worthwhile problems to solve. Then come up with hypotheses for solutions to the problems that you think will be valuable, usable, feasible and viable. Finally, you need to develop a plan to test your hypotheses as quickly and efficiently as possible so you can quickly discard the failed hypotheses and focus your resources on the ones that have merit.

Given the complexity involved, even if you follow a tried and tested product strategy framework like the one above, there are still plenty of ways that a product strategy can go wrong. Here’s a short selection of some of the common problems we’ve seen, along with our advice for addressing them, from our experience.

If you don’t have enough validated insights about your customers, you can’t accurately identify their problems and needs, or form useful hypotheses about how your product will help. Your customer insights need to be coupled with deep knowledge of your business, your capabilities, and your competition. If any of these are missing or under-done, it will undermine the basis for understanding the challenge you’re responding to and your hypotheses about how your product will meet your customers’ needs will be misinformed.

Our advice

Are you, your product team and your stakeholders really clear about who your customers are? The more clearly and meaningfully you can describe the type of people you’re designing for, the easier it is to make sure you’re talking to those people in your research. Developing personas can be a helpful way to develop a clearer sense of the type of people you should be hearing from.

Once you’ve found the right people, the actual research doesn’t have to be exhaustive or exhausting. Interviews and surveys in relatively small numbers can help to validate insights. A useful rule of thumb is that when you’re hearing the same response to your main questions repeated across research participants, you can have reasonable confidence in what you’ve learned and you can move on. Sometimes you can get to that point after four or five respondents, sometimes it can take more.

If you’ve misinterpreted what your customers have told you (or haven’t heard from them at all) you can fall into the trap of settling on the wrong problem. For example, you might think you have learned that your customers’ problem is a lack of choice and your product can solve that by offering them an array of choices. But actually the root problem may be that the current choices available to them just aren’t meeting their needs. Your customers don’t want the complexity of more choices; they just want the current options to be better tailored to their needs.

Our advice

Are your problem statements supported by evidence? Do you have verbatim quotes from your customers that speak to the problems and needs that you’ve identified? If you’re really lucky they may even articulate the exact problem for you.

To help make sure you’ve identified the right problem (and any related problems that you’ll also need to solve), you’ll need to understand more about your customers than just how they interact with your product. You also need to understand how your product fits into other parts of their lives. Probing for this broader insight can reveal customer problems and unmet needs you didn’t know about and open up new opportunities for you to explore.

There will always be more things you want to do than you have capacity for. And humans generally have a strong optimism bias, meaning that we think we can get more done than is possible (often in spite of prior experience!) A crucial – and difficult – part of forming an effective strategy is choosing what not to do.

This also means that you need to be careful about how you frame your problem statements and related goals so they’re not too broad: if they’re not precisely worded they can become a catch-all where lots of work that should be out of scope can find a home, leading to product bloat and inefficient use of your team’s time and energy.

Our advice

Using a prioritisation framework can really help with this. There are many out there, but a simple one is to do a prima facie assessment of the potential value of the problem versus the amount of effort you think will be required to solve it. Then you can then add a further filter based on how certain you are that you can solve the problem.

Depending on the circumstances, you might want to attack the problem with high potential value but a lot of uncertainty first, so you can find out if there are any insurmountable challenges as early as possible Or, if you need to generate revenue in a hurry, you might opt for a problem with lesser value that is coupled with less expected effort and greater certainty in order to chase a safer revenue stream earlier.

After all the hard work that goes into writing a strategy, it’s very tempting to print it out, stick it on a wall, and move on to the next thing. But things change, which means your strategy will need to as well. The faster things are changing, the more regularly you’ll need to revisit it. For example, at the start of the Coronavirus pandemic, most countries’ responses were based on a mitigation strategy, (remember “flatten the curve?”) But the experience of the first countries to be hit by the pandemic quickly revealed that this strategy led to overwhelmed health systems. In response, many countries (including New Zealand) quickly revised their strategy to aim for elimination of the virus to avoid overwhelmed health systems and prolonged, heavy restrictions on society. As populations became highly vaccinated, most countries relaxed restrictions and moved back to a mitigation strategy, based on modelling and evidence that infection rates could be effectively managed via mitigation.

Our advice

The solution to this seems obvious, right? Set up your regular quarterly strategy review meeting and you’re done. Not quite! Making sure you’re asking yourself and your team useful questions will help ensure that you’re giving your product strategy the level of scrutiny it needs when you review it. You want to identify what you’ve learned over the past quarter. Does anything you’ve learned challenge the assumptions, insights, and hypotheses that your strategy is based on? Has anything changed in the market? Is there a new competitor or emerging customer segment? Have you unearthed new problems or unmet customer needs that align with your product vision? Honestly answering these questions from a range of perspectives will give your strategy a robust test of whether it is still valid or needs revisiting.

Creating an effective product strategy requires the knowledge and skill to meld big-picture, future-focused, conceptual thinking with deep and detailed insights into your customers, your business and your technological capability.

Writing a strategy is inherently hard work. There is a mudslide of advice available about how to approach it. In my view some of it is useful, but a lot of it just makes the task seem bigger and more confusing. It takes quite a bit of wading through the mud to find the valuable insights and work out how to apply them.

I have found the following framework a useful starting point for writing an effective product strategy that has worked for whatever product or organisation I’ve applied it to:

Just like developing a product, it can take multiple iterations to get your product strategy right. I’ve outlined some common problems and advice for addressing them, based on our experience. But this is only a small sampler of what we’ve seen. If you want some tailored, expert advice with setting up your product for success get in touch!

Keen to get in touch? Flick us a message.

New digital project? Keen to optimise your existing digital project? We’re always keen to talk.

Made with ♡ in Wellington

© 2020 PaperKite